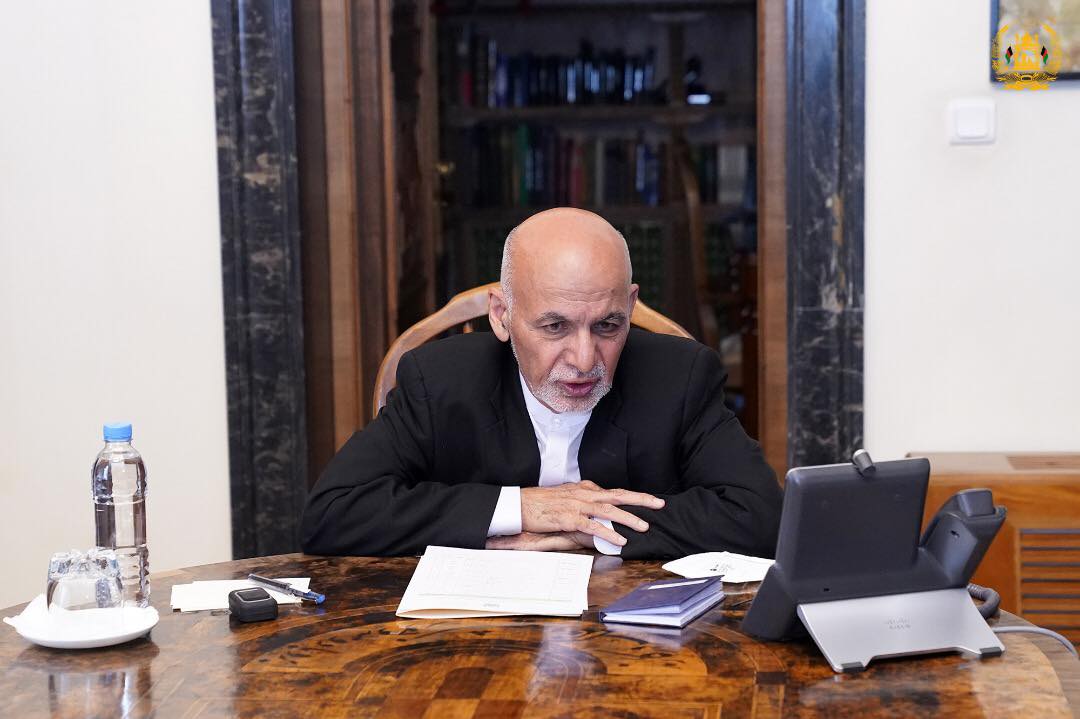

The Americans are pulling out and the Taliban are advancing on Kabul. Even Afghanistan President Ashraf Ghani is concerned about a possible civil war. In this DER SPIEGEL interview, he discusses how an escalation could still be avoided.

Interview Conducted by Susanne Koelbl in Kabul

DER SPIEGEL: Mr. President, the United States made peace with the Taliban without involving your government, and now it is pulling out of Afghanistan. Do you feel betrayed?

Ghani: Where is the betrayal? The Biden administration has made a strategic decision. They have assessed and defined their interests. I respect that. Any expression of anger, resentment or disappointment would not be productive. I myself have never opposed a U.S. withdrawal – nor do I waste my time on regrets. The question now is where our common interests lie in the future and how we will reshape our partnership with the U.S.

DER SPIEGEL: How long can your government resist the Taliban’s attacks without U.S. support?

Ghani: Forever. If I did anything, it was to prepare our forces for this situation. We have already effectively resisted the first wave of attacks in May. But are you writing about that too? We are defensible. The fundamental issue was actually the ambiguity of whether the Americans would stay or leave. That went on for two years. Now there is clarity, now a new chapter is being opened and new rules of the game apply.

DER SPIEGEL: Is this the start of a civil war like the one of the 1990s, when the Soviets withdrew with their army?

Ghani: The probability of a civil war is there. But it doesn’t have to come to that. You know, when the combat mission officially ended in 2014 and was modified as a training mission, everybody already saw the demise of the republic coming. But we made it work. Please take into consideration that all of this is also a question of narrative: The more the scenario of destabilization is spread, the more we are confronted with violence here.

DER SPIEGEL: In Kabul, the country’s elites are currently trying to form a state council across all party lines – not only to organize the peace process, but also the resistance against the Taliban. Will this work?

Ghani: The council is actually forming right now. It is emerging, and I am pushing for it with all my might. A peace process is a fundamental scenario. Once the Taliban realize that they cannot overthrow the government, they will need to come to peace as the dominant scenario.

DER SPIEGEL: Do you yourself still believe in a peace process?

Ghani: Peace will primarily be decided upon regionally, and I believe we are at a crucial moment of rethinking. It is first and foremost a matter of getting Pakistan on board. The U.S. now plays only a minor role. The question of peace or hostility is now in Pakistani hands.

DER SPIEGEL: What influence does the Pakistani government have on the Taliban’s fighting?

Ghani: Pakistan operates an organized system of support. The Taliban receive logistics there, their finances are there and recruitment is there. The names of the various decision-making bodies of the Taliban are Quetta Shura, Miramshah Shura and Peshawar Shura – named after the Pakistani cities where they are located. There is a deep relationship with the state.

DER SPIEGEL: Why didn’t the Americans intervene earlier in Pakistan to weaken the Taliban’s clout?

Ghani: You’ll have to ask the Americans that. I can empirically say that they depended very heavily on getting supplies and logistics through Pakistan.

DER SPIEGEL: Why should Pakistan change its strategy – now, of all times – when it is so close to the finish line, and when the country would soon be able to determine the course of Kabul via the Taliban?

Ghani: My visitor from Pakistan yesterday, Army Chief General Qamar Bajwa, clearly assured me that the restoration of the Emirate or dictatorship by the Taliban is not in anybody’s interest in the region, especially Pakistan. However, he said, some of the lower levels in the army still hold the opposite opinion in certain cases. It is primarily a question of political will.

DER SPIEGEL: The Pakistani army chief was accompanied by the British Chief of the General Staff General Nick Carter. What role is London playing in efforts to contain the Taliban?

Ghani: General Carter is a mutual friend. We’ve known each other for over 10 years, since he commanded the ISAF forces in Kandahar. He’s a wonderful man. It sometimes takes special people in history to come together in a crisis.

DER SPIEGEL: Is a future security agreement between Afghanistan and Pakistan the key to peace?

Ghani: Most certainly an important key. But my goal is the neutrality of Afghanistan. We don’t want a new protecting power, and we don’t want to be part of regional or international rivalries.

DER SPIEGEL: What might a communal society look like if you have to share power with the Taliban in the future? Will the men be forced to wear long beards once more and will the women not be allowed to leave the house?

Ghani: Ask the Taliban! We will not allow them to do that. The Taliban will not beat the youth of Afghanistan into submission.

DER SPIEGEL: All that has been built up over 20 years can quickly be shattered. In just one night, for example, the Taliban looted everything they could from institutions, schools and universities in a raid in Kunduz. Has all the reconstruction work by the West, including Germany’s Bundeswehr armed forces, been in vain?

Ghani: I assure you, the women will no longer give up their rights here, nor do they need foreign advisers to represent them. Thirty percent of the administration are women, 58 percent of government officials are young, well-educated people under 40. Our army is a volunteer army. Afghan society has a lively discourse among itself; it makes sovereign decisions. I think this awareness in society is irreversible.

DER SPIEGEL: And what if the Taliban do seize power? Will neighboring countries and Europe have to brace themselves now for a new wave of refugees as they did back in the 1990s and, most recently, in 2015?

Ghani: This narrative of gloom and doom must stop. The more the media talks about these doom-and-gloom scenarios, the more it encourages people to leave. Instead, please describe the opportunities that are available here, even in the most difficult of times, including war.

DER SPIEGEL: Do you have an example of such an opportunity?

Ghani: Of course. Afghanistan is the world’s largest producer of pine nuts. For a long time, pine nuts were smuggled to Pakistan and then to China for further processing. Through an agreement with a Turkish airline, we can now bring them directly to Germany. Over the past 20 years, we have trained many capable young people who can communicate with the world. We are building on digitalization, all of which creates jobs, and jobs mean stability.

DER SPIEGEL: What can Europeans contribute to the peace process with the Taliban, especially the Germans?

Ghani: They can do a lot. After all, Pakistan is a state; this state has to make an important decision now. Clear messages and incentives from Germany will help – and, conversely, they should introduce sanctions if the decision goes in a different direction than hoped. As Europeans, you should not see yourself as observers; you are a direct part of these events.

DER SPIEGEL: Can you protect the local employees of Western organizations from being hunted down by the Taliban as collaborators? Or the Shiite minorities who are threatened as so-called “infidels”?

Ghani: We are working with our security forces. Some people will undoubtedly still make their way to Europe, but we do not encourage them to do so. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has shown outstanding leadership in the crisis by accepting and integrating refugees in Europe; she upholds human and constitutional values in Europe. We are very grateful for that. But we have to make it clear to people here that being a refugee in Greece or in Turkey or in the Mediterranean is no bed of roses. For those who have worked with the coalition, we should make offers that encourage them to stay here. What are they going to live off? The more you help us stabilize Afghanistan, the fewer refugees there will be.

DER SPIEGEL: What could persuade the Taliban to opt for peace after all?

Ghani: In any case, Western diplomacy should stop coddling them. The Taliban are criminals. They kill innocent people – as they did just a few days ago, in an attack on a girls’ school in Kabul, in Dasht-e-Barchi, which cost the lives of 85 people. Do not validate these criminals as a shadow government!

DER SPIEGEL: The Taliban claim they had nothing to do with the attack, saying that Islamic State was behind it.

Ghani: You know, I usually have a heart of stone, but this crime has affected me deeply. The Taliban made the environment for these crimes possible – they did not cut their ties with al-Qaida, as they claim to have done. They bear responsibility for this.

DER SPIEGEL: While many people in the country hate the Taliban, they also reject your government. Corruption has reached intolerable levels and, at the same time, more than 50 percent of Afghans still live below the poverty line. Why is that?

Ghani: Being disappointed with your government is the right of every citizen. However, we must keep in mind that the main driver of corruption for a country in crisis is uncertainty. When people think “tomorrow this system will no longer exist,” their first thought is to focus on what they can gain for themselves during that time.

DER SPIEGEL: Have you also made mistakes?

Ghani: Most international money does not go to the government. Some contracts are resold up to six times, until a project is built from the pitiful remainder. We have established institutions, which ensure corruption is being pursued. The judiciary is working. Some of the corruption in Afghanistan also stems from the criminal economy of drug trafficking. Don’t forget that the list of 5,000 prisoners released through Taliban negotiations with the U.S. included 60 of the most notorious drug smugglers.

DER SPIEGEL: Do you regret giving in to these Taliban demands to make the peace deal with the U.S. possible?

Ghani: We were told that it would bring us closer to peace. But did the violence go down? No, it went through the roof. I hope our international partners learn a lesson from this.

DER SPIEGEL: Right now, there is again talk of releasing another 7,000 Taliban members from prisons as a precondition for peace talks. Will you agree to that?

Ghani: Only if it leads to a comprehensive peace agreement.

DER SPIEGEL: Being the president of Afghanistan is probably as demanding as riding a tiger. How much stress does your job put on you?

Ghani: To relax, I read, at least an hour every day. Right now, I am reading a book about the third sector, civic engagement in Europe and also a selection of Persian poetry. When I was young, I could memorize 5,000 poems; now, my mind is occupied with other things.

DER SPIEGEL: How confident are you personally about the future of your country? Are you afraid that if everything goes wrong, you’ll end up having to leave Kabul on the last plane, like the Americans did in Vietnam?

Ghani: I know I am only one bullet away from death. There have been many attempts on my life. But Afghanistan is not South Vietnam, and I did not come here in a coup. I was elected by the people. I’ve never had an American bodyguard or an American tank protecting me. Before I became president, I lived abroad for 28 years, and had a successful career. But I was not happy. No power in the world could persuade me to now get on a plane and leave this country. It is a country I love, and I will die defending.

DER SPIEGEL: Your place is here?

Ghani: Whatever may come.

DER SPIEGEL: Mr. President, we thank you for this interview.